Biography

Julian Germain (b. 1962) became interested in photography at school and went on to study it at Trent Polytechnic in Nottingham and the Royal College of Art in London. For more than 30 years he has used photography as a vehicle for exploring the world, examining social themes and producing numerous books and exhibitions.

He is well known for his appreciation of archival, amateur and functional photographs and for including them alongside his own pictures in projects such as Steel Works (1990), In Soccer Wonderland (1993) and For every minute you are angry you lose sixty seconds of happiness (2005). Photography’s place in our everyday culture is one of his central concerns and he is one of the founder members (and sits on the editorial board) of Useful Photography magazine.

The experience of collaboration and engagement are also significant, clearly visible in his series of large-format group portraits (Classroom Portraits, 2012) and developed further in the long standing project No Olho da Rua (ongoing since 1995), which is founded on principles of shared creativity with artist colleagues Patricia Azevedo and Murilo Godoy and people living rough on the streets of Belo Horizonte, Brazil. In 2020, the publisher Mörel will begin the release a series of 18 booklets, each focussing on a different theme from the No Olho da Rua archive.

Portfolio

Hidden Presence

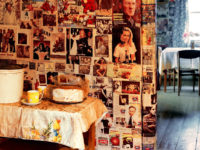

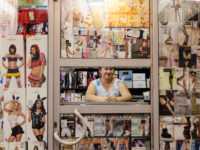

One of the recurring themes in Germain’s work over the years has been time, the effects of its passing, memory, the legacy of the past and prospects for the future, even if the wider context may have been education, family or football.

His photographs from the former British colony of St Kitts in the West Indies and the Chepstow, Cwmbran and Newport area of South Wales are an attempt to respond to historical links between the two locations alongside contemporary issues. The sugar industry, slavery, colonialism and migration - the movement of people across borders and continents - are at the heart of the story, with particular reference to Nathaniel Wells who was born into slavery on Vambelles Estate in 1779, the illegitimate son of a Welsh merchant sugar plantation owner and one of his slaves. Extraordinarily, at the age of 9 he was sent to school in England and he later inherited his father’s plantations, making him, a person of mixed race, one of the wealthiest young men in Britain. As such he was able to purchase the magnificent Piercefield House in Chepstow which was one of the finest properties in the country, although it is now an abandoned ruin, despite its historical importance and protected status.

In Britain today, the evidence of slavery can only be seen with the help of knowledge, an understanding of how and where the vast wealth acquired from sugar was spent. The issue of migration, however, is ‘live’ and the emergence of ‘hand car wash’ businesses across the country is one of its visible manifestations because almost all of them have been set up by eastern Europeans or by Kurds seeking asylum from Iraq, Iran or Syria.

The enforced migration of the slave trade was, of course, central to the establishment of St Kitts as an economic powerhouse of the British Empire in the 18th Century. Several generations may have passed since slavery was abolished (and St Kitts secured its independence in 1983) but that history of sugar and slavery is all around the island; the ruins of sugar works (production finally ceased in 2005), self-seeding cane growing wild, an impressive British fortress and especially in the names of the people. Most Kittitians are descendants of slaves and they still bear the surnames of the plantation owners that were assigned to their ancestors.

Portfolio

Classroom Portraits

"Considering the importance of school, it seemed strange to me that the subject was so rarely dealt with as a theme in visual art. Accordingly, I began making these large format portraits of classes of schoolchildren in their classrooms. The aim was to make a straightforward record of the space and the pupils in the finest possible detail. I never tell the students how they should look but ensuring that everybody has a clear view of the camera requires concentration and patience. Each pupil has to be aware of their place in the picture. In order to achieve sharp focus in both fore and background, the exposure time is usually a quarter or half a second, so the pupils have to be 'ready' for the moment the shutter is released. I am waiting for them and they are waiting for me. The process itself generates an atmosphere and the time captured in the portrait seems significant." Julian Germain