Biography

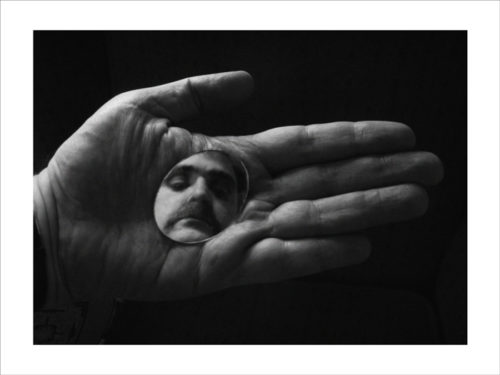

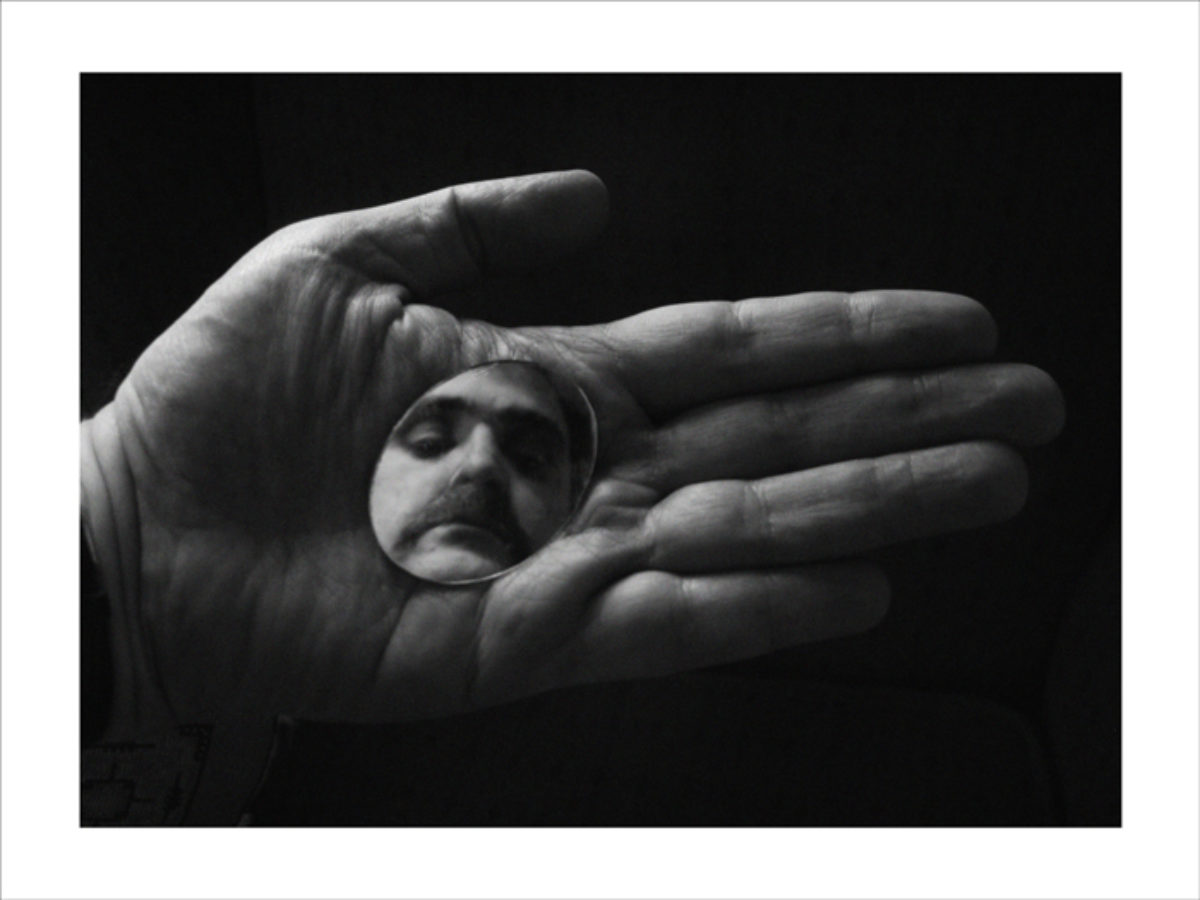

Daniel Blaufuks (b. 1963) uses mainly photography and video, presenting his work through books, installations and films. He has a predilection for issues such as the connection between time and space and the representation of private and public memory.

Blaufuks work explores the processes of memory – how we construct meaning in our lives through the accrual of details and traces, from the mental residue and after-images of our daily existence. Blaufuks is interested not only in the ways that photography and film are changing as media, but also in the methods by which we archive, store and retrieve information – our ability to remember.

Portfolio

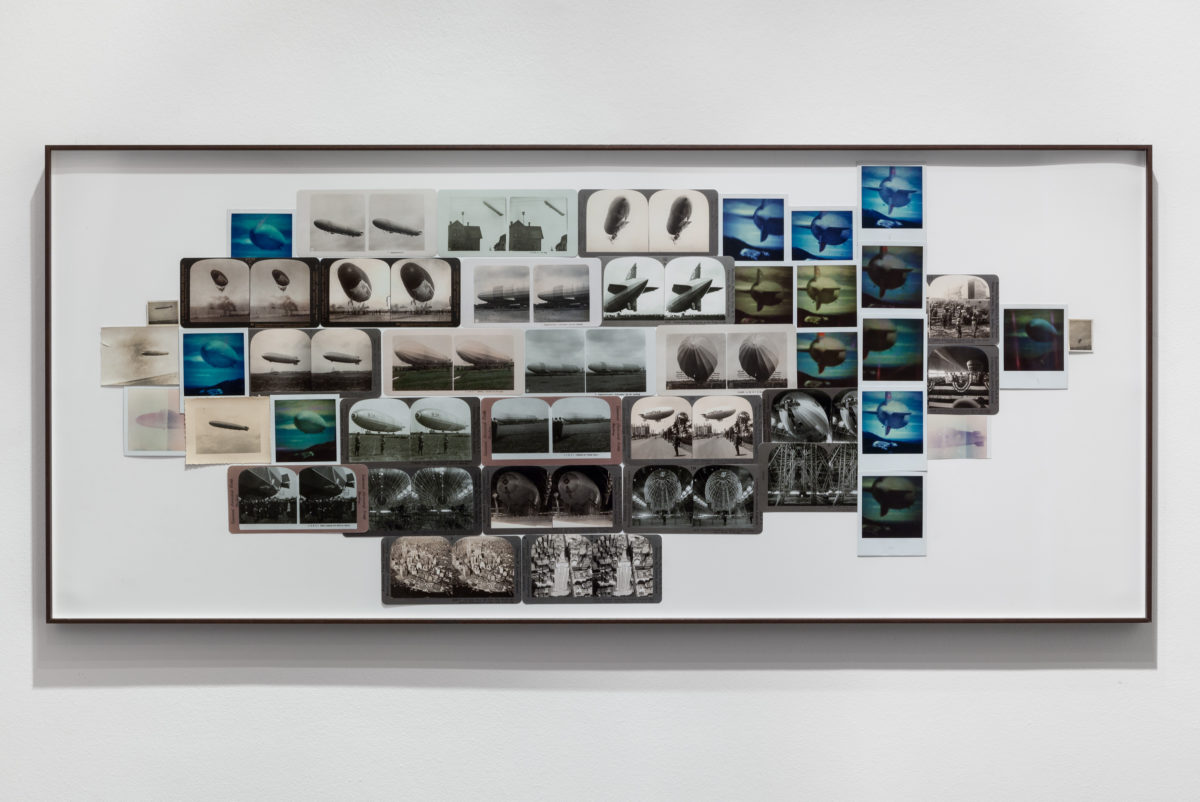

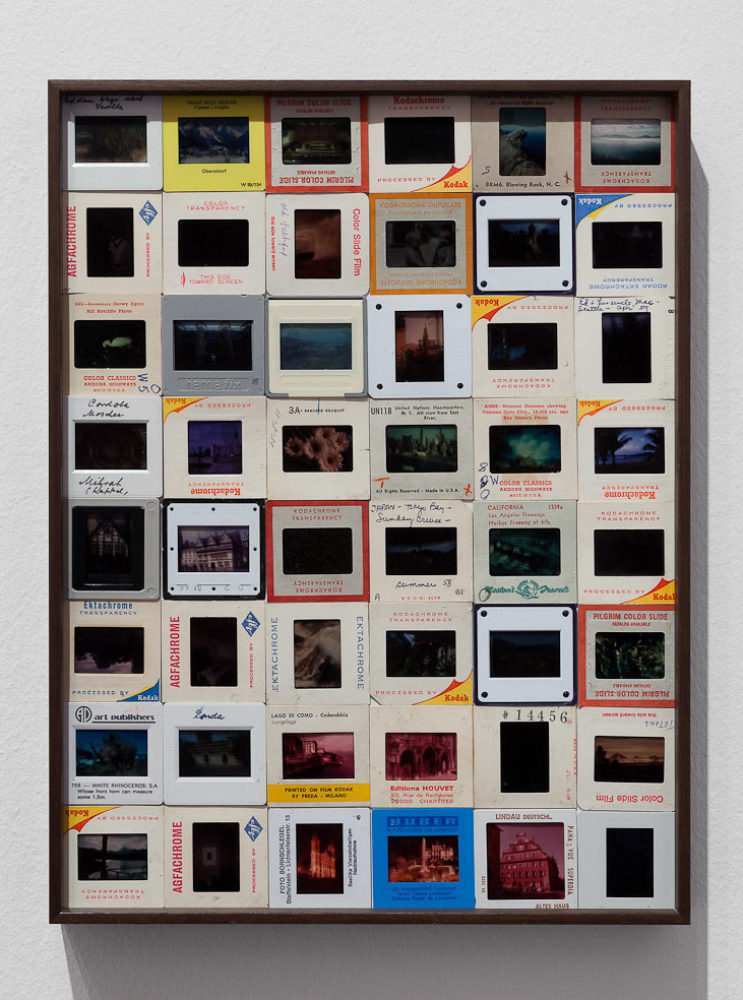

Utz

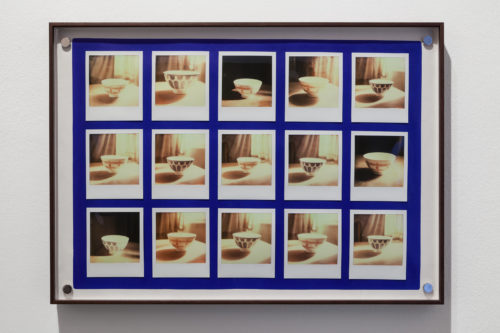

"The works in this exhibition pursue two mutually interdependent lines of investigation: one is the obsolescent and the other is auratic. At once fascinated and troubled by the disappearance of analogue photo technologies, Blaufuks revisits them at different stages throughout the historical evolution of photography, in order to determine to what extent they now possess, if any, aura– and those things that underpin it, i.e., authenticity. While referencing a whole host of historic and modernist figures from Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, the 18th century Frenchman credited with the production of the first photograph, to Man Ray, the technologies used by Blaufuks range from the cyanotype to polaroid as well as video, some of which are bona fide, such as his use of old polaroid stock, while others are patently counterfeit, such as his variously manipulated cyanotype (here provocatively denatured into outsized digital prints). In more or less every instance, the goal revolves around specific questions of aura and obsolescence. For in the artist’s estimation of things, it could almost be read as a kind of equation: the existence of aura is virtually proportionate to how obsolete the technology is. I say virtually because this is as much a hypothesis as it is an assertion. One intuits that Blaufuks acts almost like a scientist here – granted a scientist with a conspicuous agenda, but one who is sufficiently disinterested to allow that agenda to be challenged by the results of his research."

Chris Sharp

Portfolio

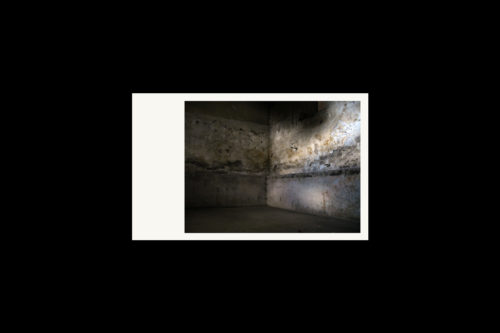

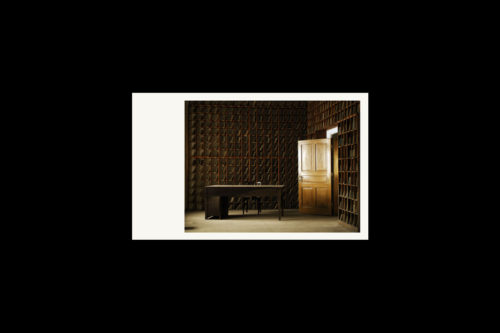

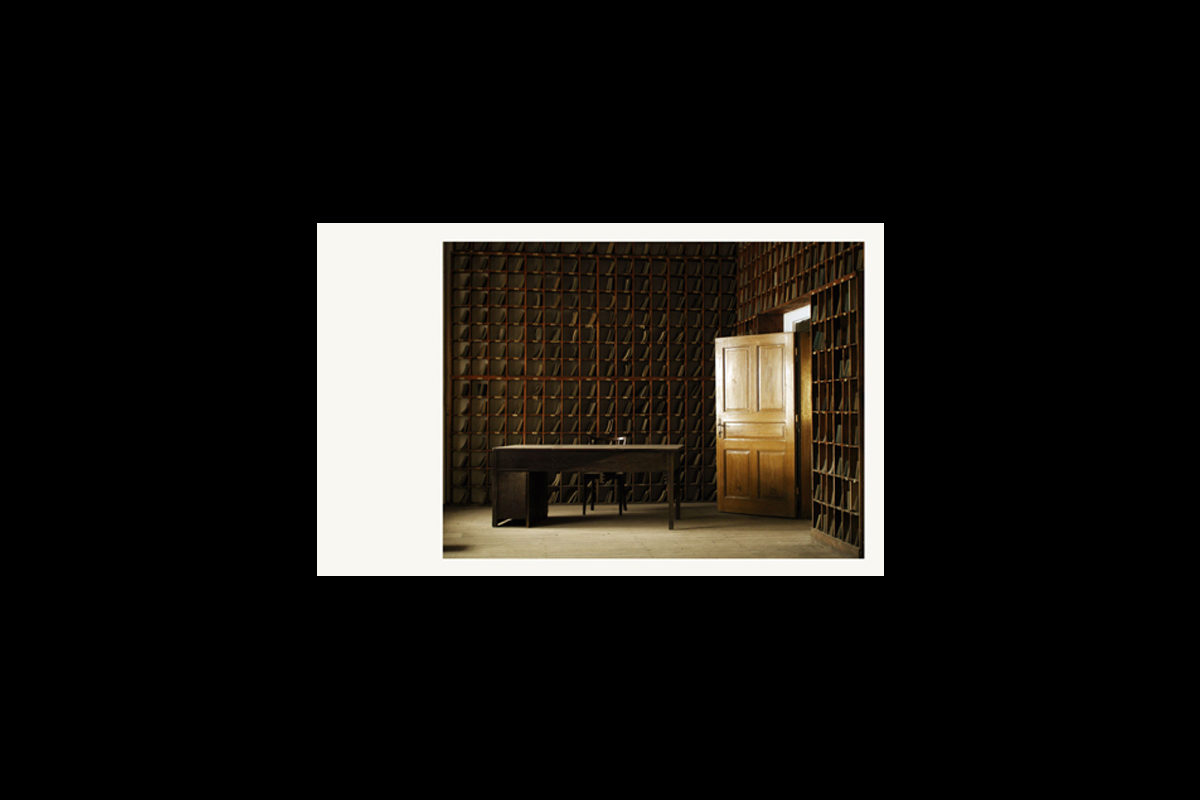

Terezin

Terezín (or Theresienstadt) is to the north of Prague, in the Czech Republic. It is a fortress which in 1942 was declared by the Germans as a “model ghetto” at the Wannsee Conference. It was controlled by a Jewish council, and it housed a grea tnumber of teachers, artists and writers. There are evens signed that there was intense cultural activity. As one of the prisoners wrote, “Life could seem almostnormal here”. But the truth is that Terezín was just one of several concentration camps en route to Auschwitz or Birkenau.

In 2007, Daniel Blaufuks travelled to Terezín, his curiosity sparked by a photograph found almost at the end of the book Austerlitz by the German author W. G. Sebald. It is the picture of a room with shelf-lined walls, with two tables,several chairs and a clock, showing six o’clock. Blaufuks found this room, which since then has been used for other purposes and no longer has the clock. Subconsciously, Blaufuks took a similar photograph to the one in Sebald’s book,which marked the start of his project Terezín: a work about the possibility (the need) to make a mental and critical revisiting of a place and a story, in a format including photographs, videos and a book.

Portfolio

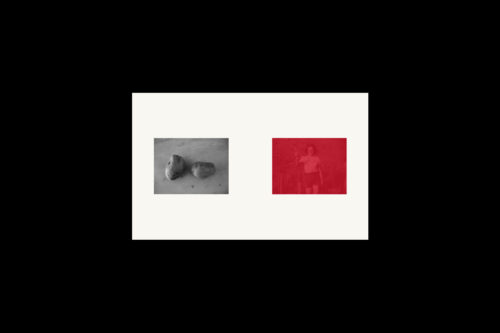

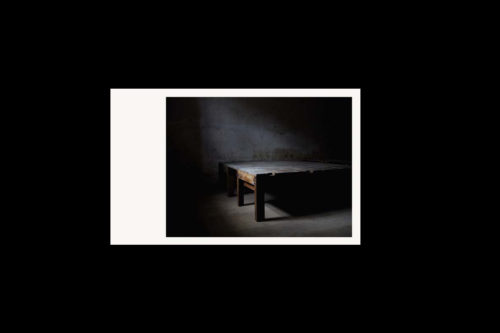

The Business of Living

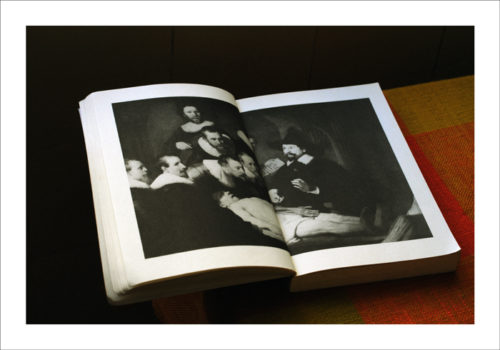

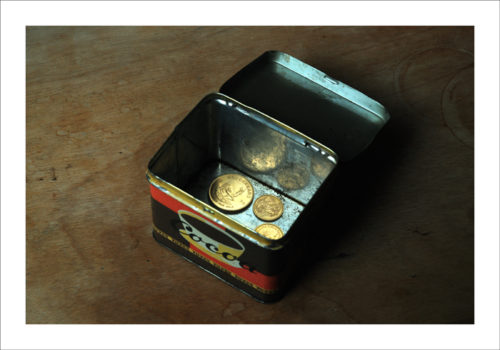

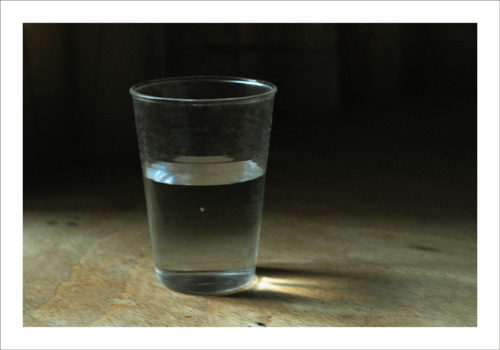

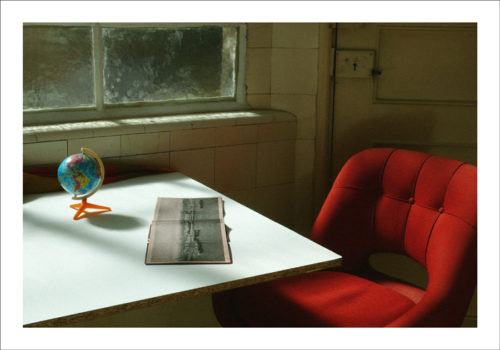

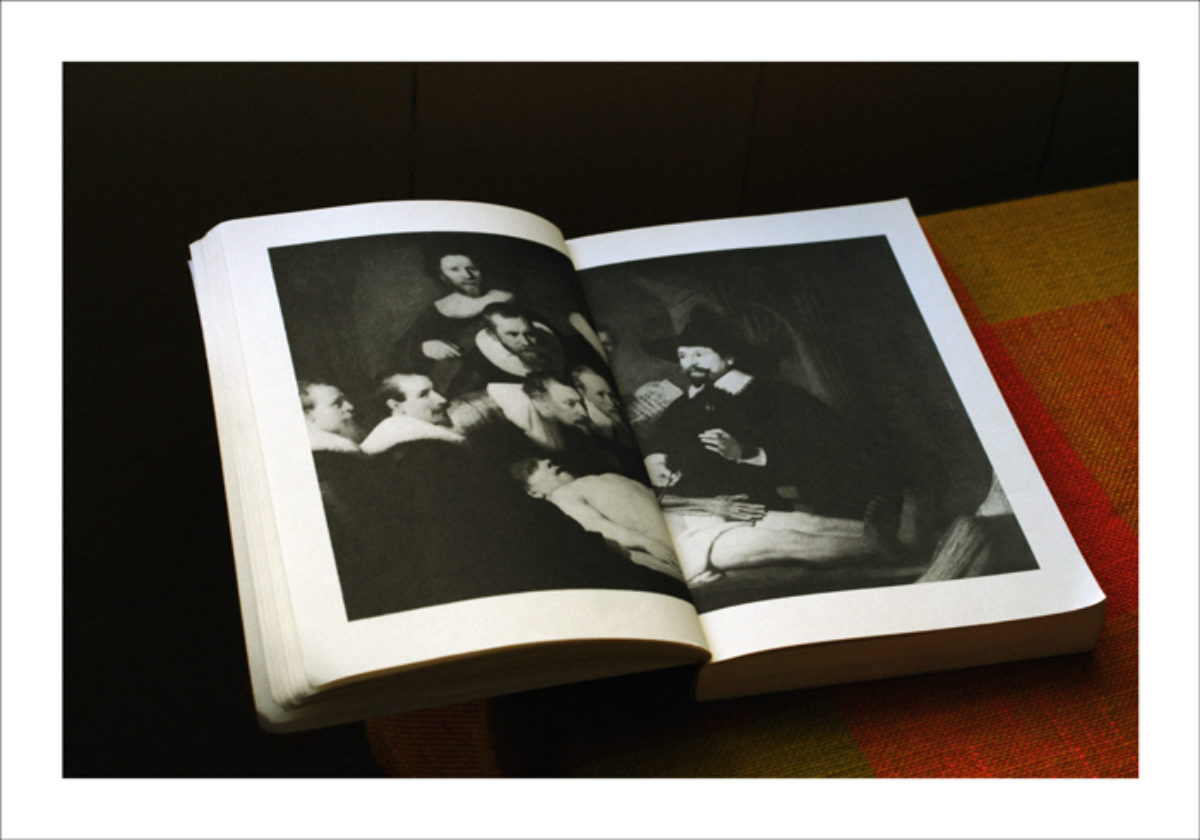

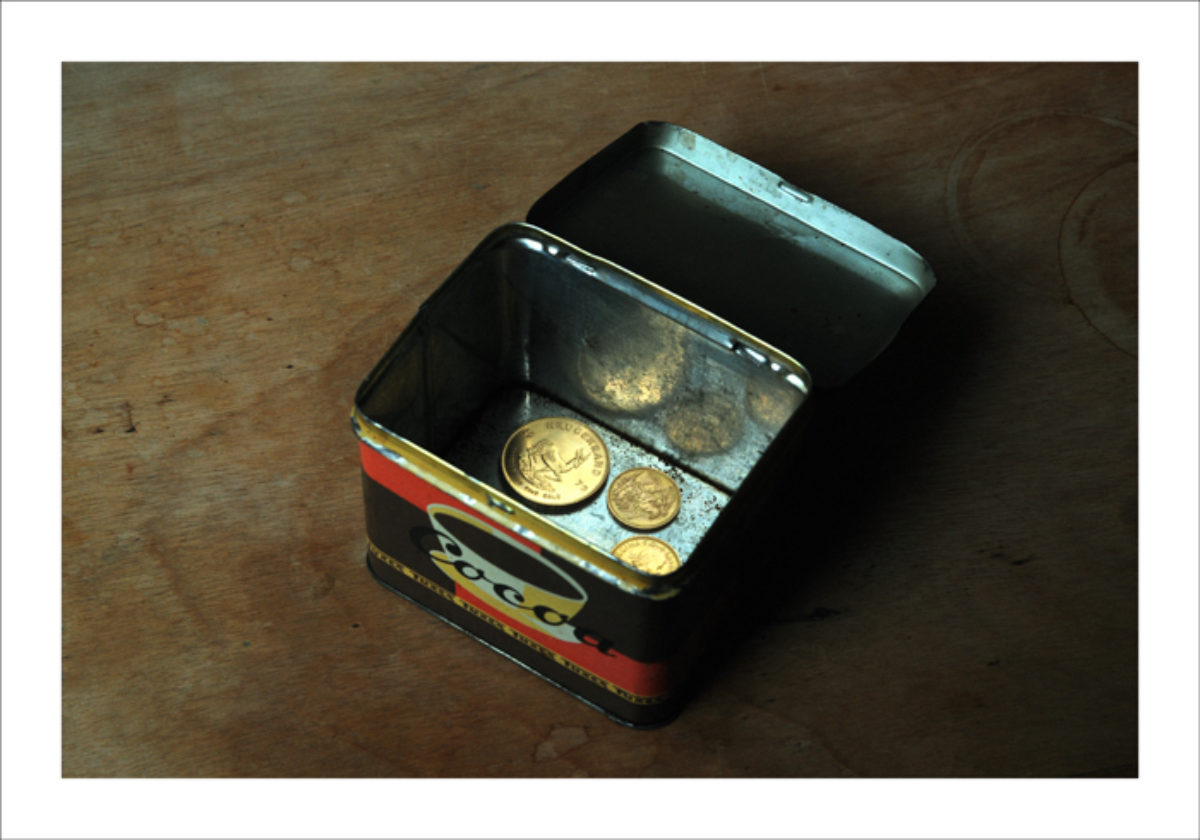

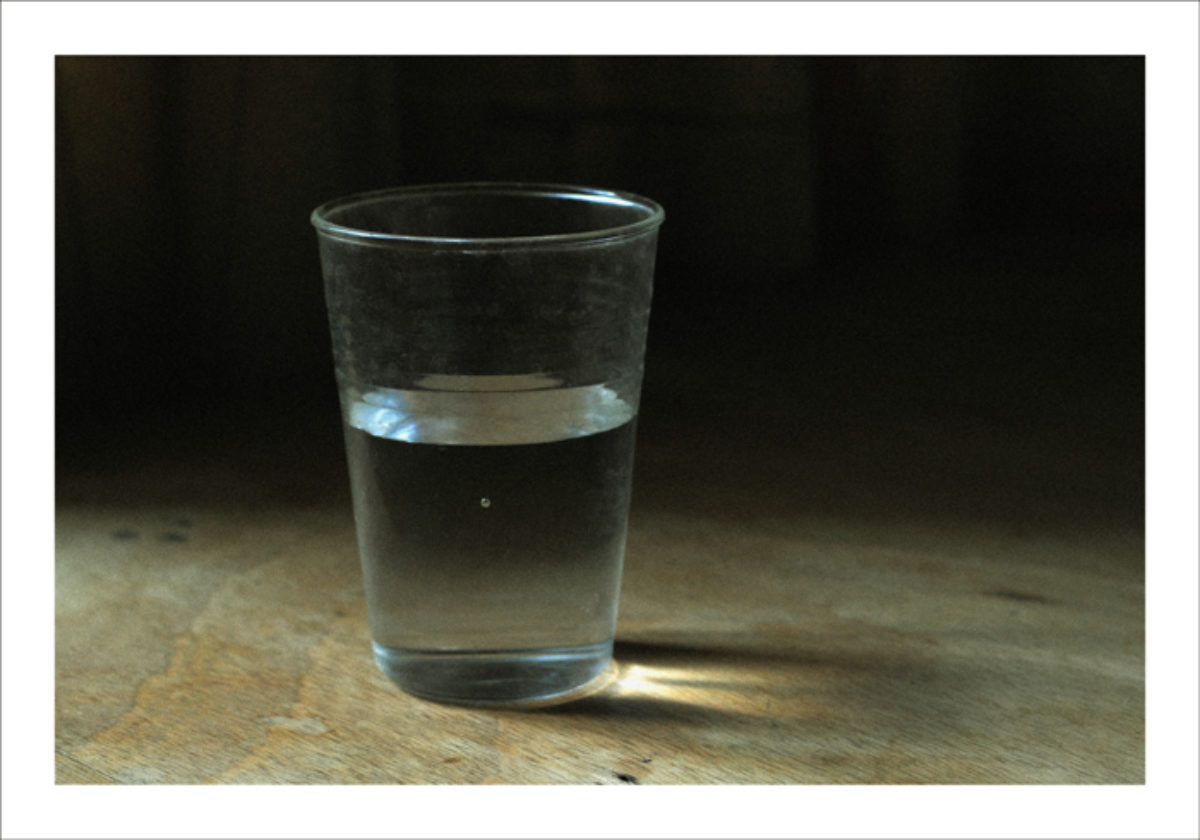

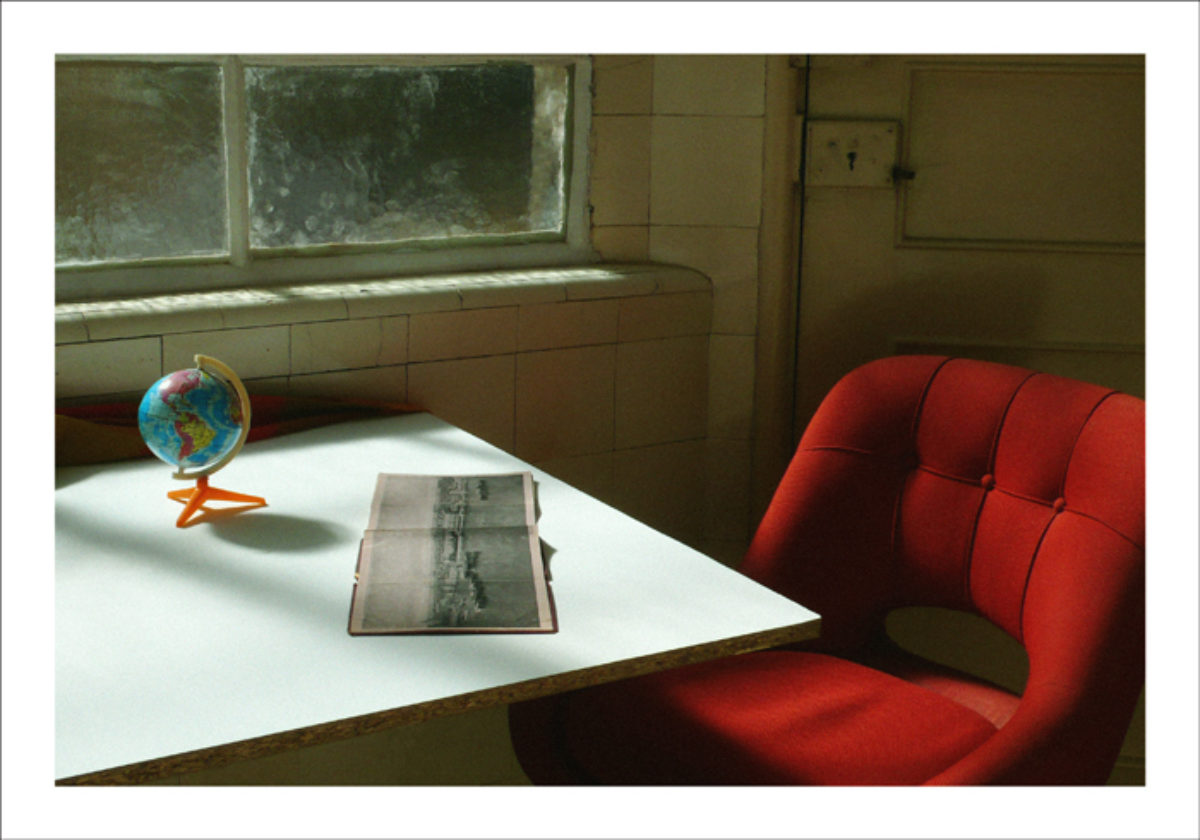

The Business of Living is a work, inspired by the diaries of Cesare Pavese, about the experience of time and the reminiscence that stays from the passing days. To live like one does a task, like something that needs its own proper order, as if it was something one has to do in some office, and the necessity, often mechanic and bureaucratic, of ordering time: to wake up, to eat, to think, to do, to work, to sleep, to live. Yesterday, today, tomorrow.

This series of works, presented in different sizes, are fragments chosen from a past life and of a space of complex time for the author. The series is composed by simple photographic works, almost “tableaus” on the banality of the daily, staged for this work in closed spaces and with very little or no connection to the outside world. They are pieces turned towards itself, as if part of a diary of a time that seems to be endless. The photographs, with a very strong symbolic language, that apparently seems to tell little or nothing at all, recall not only our personal memory, but also representations present in Painting and Cinema, and which are therefore part of the memory shared by our civilization.