Biography

Eugenia Maximova (b. 1973) a Bulgarian-Austrian photographer based in Vienna. She has a master's degree in journalism and communication studies from The University of Vienna. Photography came into her life unexpectedly but it quickly became her favoured means of communication; a new outlet of creative expression for how she felt about both herself and the world around her. Eugenia's journalistic background informs many of her art projects. Whether in her portraits, cityscapes or still life series, there is always a socio-political angle that her photographs address and seek to challenge.

Eugenia has published several books and her work has been shown in exhibitions all over the world. She has also taught several workshops.

As freelance photographer, her list of clients includes GEO, National Geographic, Die Zeit, Moscow News, The Guardian, The Washington Post, Corriere Della Sera and many more.

"Looking through the viewer and pressing the camera button helped me to escape the harrowing reality of loss, to overcome the shock and lessen the burning pain. As time passed, photography became my favoured means of communication; a new outlet of creative expression, for how I felt about both myself and my perception of the world around me" says Maximova.

Portfolio

Silent River

On October 6, 2018, 30-year old television journalist Victoria Marinova was brutally raped and murdered in the Bulgarian city of Ruse. In broad daylight, the young woman went for a run in a popular riverside park by the Danube from which she never returned. Her body later was found dumped in the bushes, battered beyond recognition.

The case caused an outcry in international media since Marinova was one of the few journalists who dared to speak up against the largescale corruption taking place in her country. Her violent death cast a stark spotlight not only on the widespread bribery involving the highest Bulgarian government circles but also on the unsafe working conditions for journalists. Reporters Without Borders ranked Bulgaria 111th out of 180 countries worldwide in their annual world press freedom index, which is the lowest in the European Union by far. The debate, however, silenced as abruptly as it began after only a few days when 20-year old Severin K. of Roma descent was arrested as the alleged perpetrator and Bulgarian officials were quick to announce to the world that the deed had not been politically motivated but was merely a tragic coincidence.

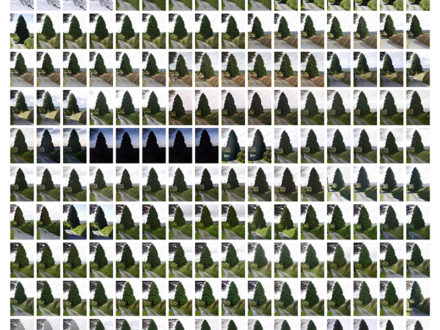

While the case no longer makes headlines and Severin K. in all likelihood will be convicted for murder, Eugenia Maximova investigates in her current photo-project “Silent River” the wider circles and preconditions of this brutal death by the Danube. Applying both an artistic as well as a documentary approach, Maximova challenges the silence that so “conveniently” shrouded the case after only 48 hours. Setting out to capture the first 365 days with her middle format camera, Maximova addresses the broader socio-political aspects as well as the personal consequences that the murder of the young woman entailed for those she left behind: her friends and family, foremost her seven-year-old daughter. In the spirit of the famous saying “the personal is political”, Maximova sets out to look for answers both as a woman, mother, journalist, artist and – bereaved. While Victoria Marinova’s murder may or may not have been connected to her work as a journalist, the fact remains that right in the middle of Europe, just by the beautiful Danube, we have a country that joined the EU in 2007 and that has a desolate human rights record: with widespread corruption and collusion between media, politicians, and oligarchs, an inefficient judiciary, repression of journalists, violence against women, and massive discrimination of the Roma community with pervasive poverty as the result. In the run-down quarter Severin K. grew up in, people don’t believe that he has committed the crime, but that he was selected as a scapegoat in exchange of money. “Silent River” is as much a subjective elegy as much as an uproar against the dismal enabling situation of modern-day Bulgaria.

Point of departure of the photo-project “Silent River” by Eugenia Maximova is the murder of Bulgarian journalist Victoria Marinova in October 2018.

Victoria was Eugenia's sister in law and mother of her 7 years old niece Sophia.

Combining both an artistic as well as a documentarian approach, Maximova investigates the wider circles and preconditions of the case capturing both the socio-political aspects as well as the personal ones. While the murder may or may not be politically motivated, Bulgaria is a country with a dismal human rights record including widespread corruption and severe threats against press freedom. As such, “Silent River” sets out to document the first year after Victoria Marinova’s untimely death in search of answers, manifesting the void as a protest against the injustice it bears witness to.

Portfolio

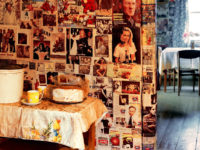

Kitchen Stories from The Balkans

The people of the Balkans live in the shadow of a long history of wars, conflicts and unresolved ethnic tensions. Much of the energy that could have gone into building a future has been squandered on maintaining those tensions and the result is an impoverished present. Young families must either pay exorbitant rents or live packed like sardines in their parents apartments. And most of those apartments are in the hopelessly ugly, crumbling concrete blocks which are the legacy of the communist era.

The term Balkan whether it is describing a culture or a geographic area, usually has a strong suggestion of the rural with a heavy overlay of the Orient. In whatever context it is used, the word reverberates with cultural and sociological connotations, with a sense of division and disagreement. The kitchen is a multipurpose room, a space which reflects identity and self-perception. It embodies the spirit of the Balkan home and mirrors society as a whole. The functional, unadorned style which results from this conveys a tangible sense of the region’s lost identity, the inevitable legacy of half a millennium under the Ottoman yoke and half a century behind the Iron Curtain

Portfolio

Destination Eternity

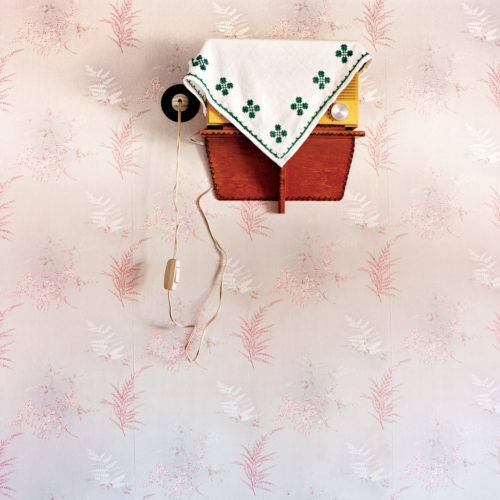

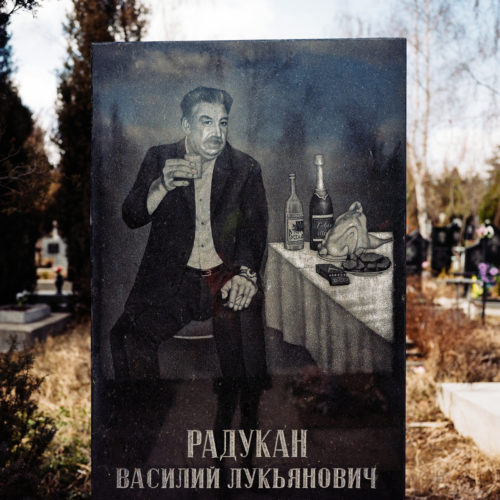

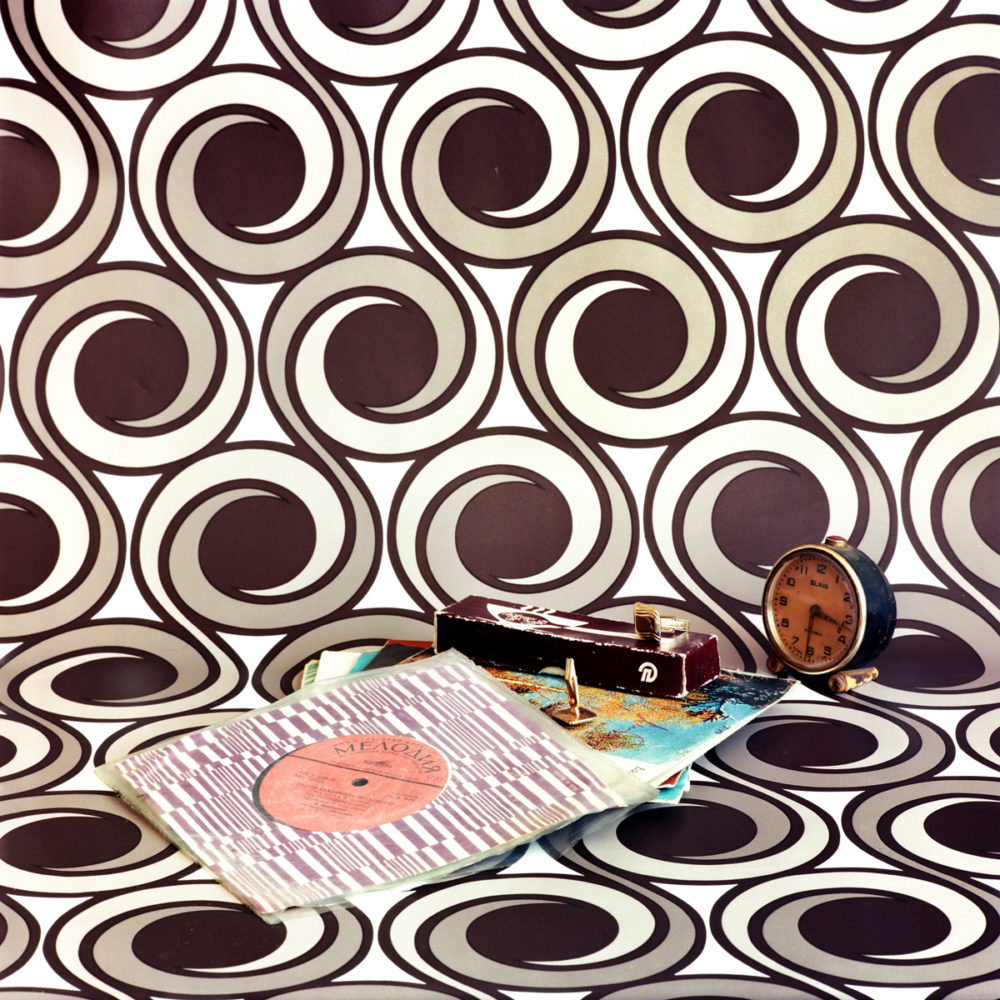

In the last years of the 20th century, shortly after the collapse of the Soviet Union, all of the

sudden a whole new cemetery culture emerged in its former territories. This new trend manifests itself in

eccentric naturalistic engravings emerging out of black marble plaques, some enormous, others smaller in

size. Motives can vary greatly from simple portraits to luscious landscapes, complex locations and bizarre

collages.

The origin of this new fashion is generally unknown. The trend might have been set, as

some suggest, by the post soviet mafia, which became a reference model in the early 90’s.

However,

its roots can be found hidden in the past, in the strong relationship between totalitarianism and kitsch.

Back in Soviet times, kitsch was the most common and only affordable form of aesthetics and decoration.

Kitsch has shaped life and formed soviet mentality for many years.

Many of those graveyards are

not only a form of expressing grief, in addition, they celebrate the lifestyle, social status and financial

power of both those who are dead and those who are still alive.

With recent advances in

technology, there are more possibilities available to those who are interested in this phenomenon. They

range from a new kind of colored engravings, instead of the usual black and white, to the possibility to

order real installations of all imaginable forms out of various desired materials.

Portfolio

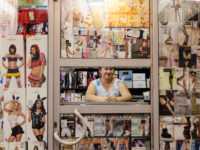

Associated Nostalgia

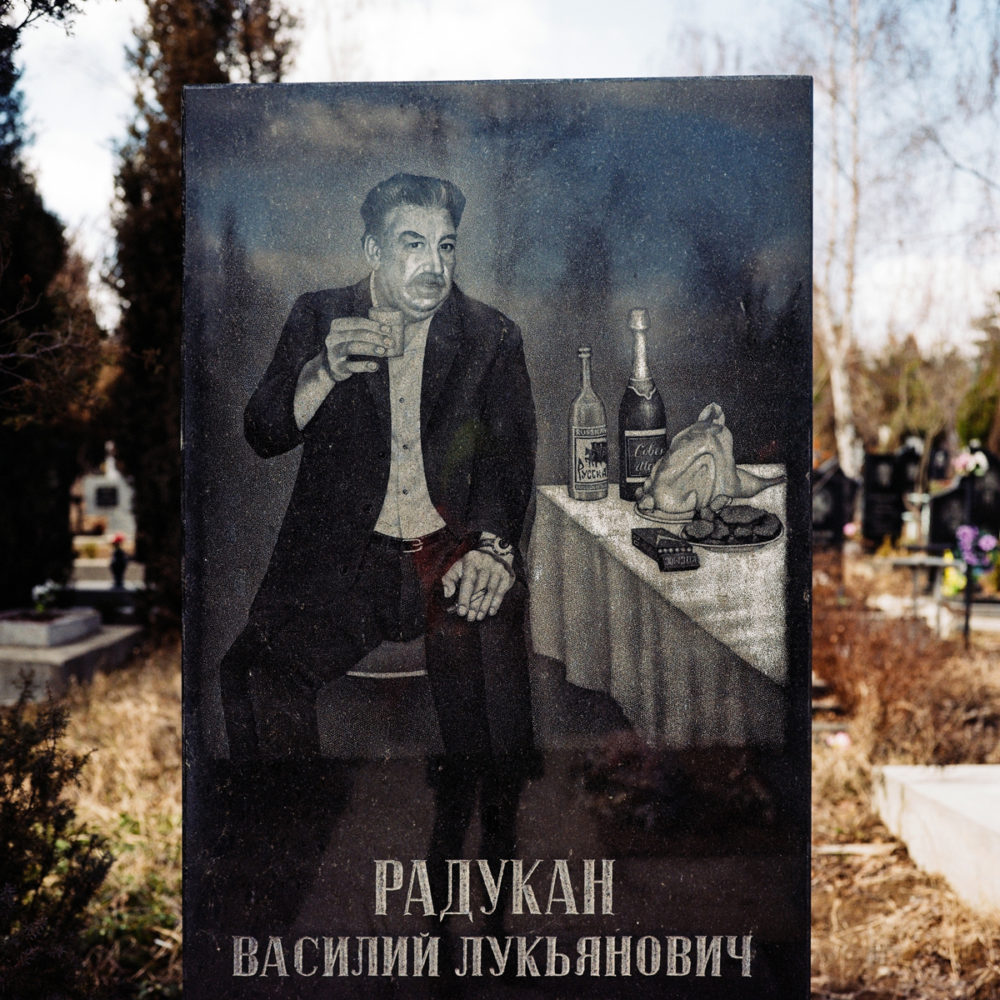

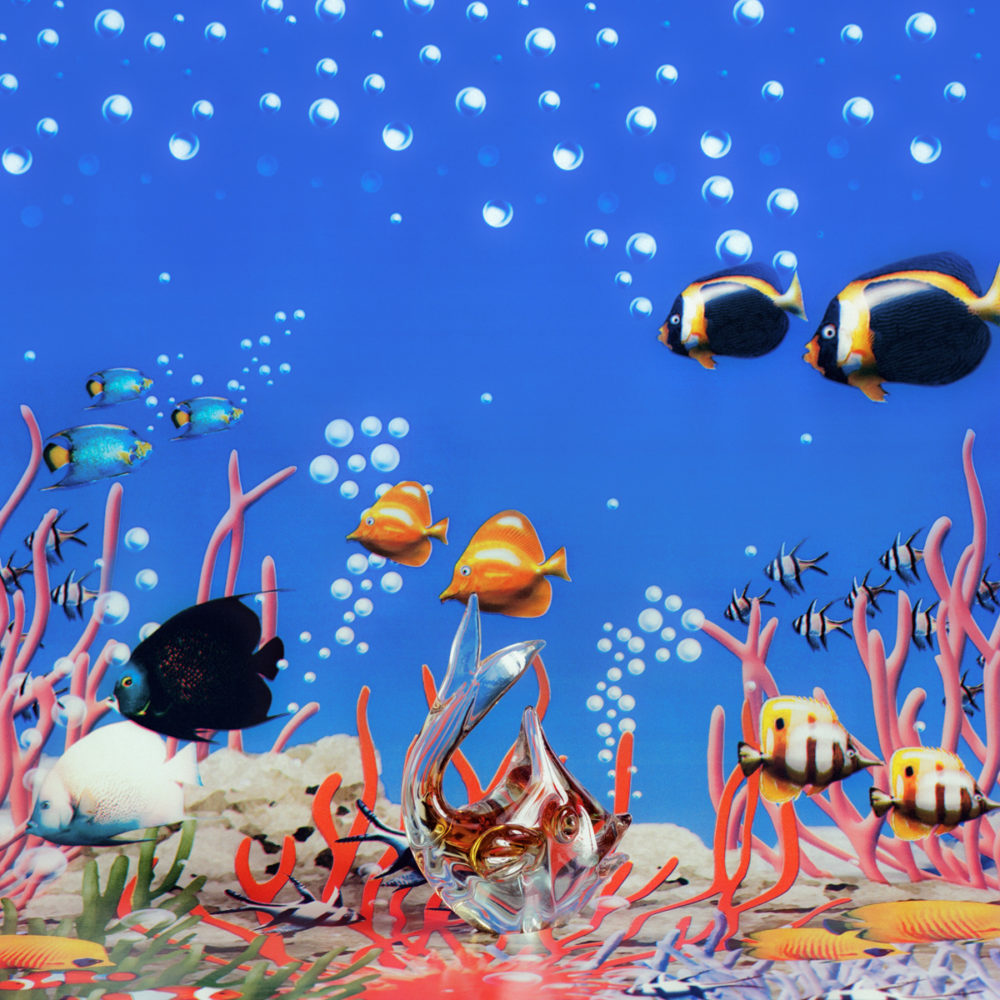

“Kitsch and the human propensity for exaggerating have always fascinated me. Many of my childhood

memories relate to kitsch. It was on open display in almost every household growing up – crystal and ceramic

dinner sets, vases and figurines, hard-to-acquire foreign objects, plastic fruit and flowers. They were

showcased behind glass and were the pride of the house. The scarcity of goods during communism created a

culture of showing off, in which people behave ostentatiously.”

Kitsch is melodramatic,

sentimental and folksy, but it also entertains. The kitsch culture of today flourishes across all areas of

life. Kitsch is visual fast food- sometimes difficult to digest, but for many it is also unpretentious and

tasteful.

Eugenia Maximova